In Chilliwack, the students were aware of the women’s liberation movement that was going on, and perspectives on gender were changing among students. Not all were massive proponents of the women’s liberation movement, but students were certainly aware of the movement; many embraced it. It was clear, that attitudes and perceptions of gender ideals were changing among students, but this came with a lot of skepticism which would be expected of Chilliwack at this time.

One female student, Cindy Ryall, expressed some hesitation toward the movement. She said, “I’m not really that into the Women’s Lib movement… I enjoy having doors opened for me, having older men call me Miss and guys treating me as if I were fragile.”[1] Cindy continued and argued that women were, in fact, more emotional than men and that it was good for women like her to have a man for support.[2] Now, Cindy did still express support for the idea of equal pay on the condition that the woman was able to do as good a job as a man could do.[3] Her endorsement of equal pay was about as far as she went in her support for Women’s liberation; instead, she expressed that she enjoyed being female and did not wish to be equal to men.[4]

Another student, Judy Mcleod, had a different perspective on the Women’s liberation movement. She did reject the protest, sign-waving part of the movement as she did not think women needed to protest to prove their equality with men.[5] Just because men are under the illusion that they are the “stronger sex,” does not mean that they are; it was just “wishful thinking.”[6] Judy wrote, “Women don’t deserve to gain equal wages, or any other equality with men if they have to gain these by demonstration and protests.”[7] She argued further that it is a crime to pay a woman less for the same job, yet it happens because men control the pay levels.[8] She wrote, “Man [sic] seems to hold most executive positions these days, but they would be lost without their secretaries around to show them how to spell.”[9]

Judy suggests that while the situation women are in is because men hold the power, women also have some of the blame too. She argues that women should not be content to be at home, making dinner for their working husbands, and this contentment contributes to the problem.[10] Men have learned to expect this behaviour, according to Judy, and they still expect it.[11] Judy suggests that women should drop the home work and instead shock men by starting to take their jobs in offices; women should shock men by proving their capability in the offices, in that they can do the same work, just as well as the men.[12] Judy is not arguing for massive protests to bring change, but instead, she envisions a silent movement to push women into new roles where they can make new rules as well as some money.[13]

One debate that the teens of CSSS engaged in was whether or not women had to wear a bra. There were different perspectives on this, both with the women and the men. One girl wrote that she felt embarrassed by the other girls who did not wear bras; other students wondered how this girl could feel embarrassed by the actions of others.[14] The majority of the girls, however, disagreed with the one girl who was embarrassed; the girls of CSSS largely thought that they had every right to go braless.[15] They argued that there was nothing wrong with it, and it was more comfortable.[16] The boys of CSSS had ranging opinions from those who admitted they liked it, and those who did not care at all.[17] The fact that this debate happened was evidence of the changing perspectives, because this debate was considered relevant enough for the student newspaper to ask student opinions.

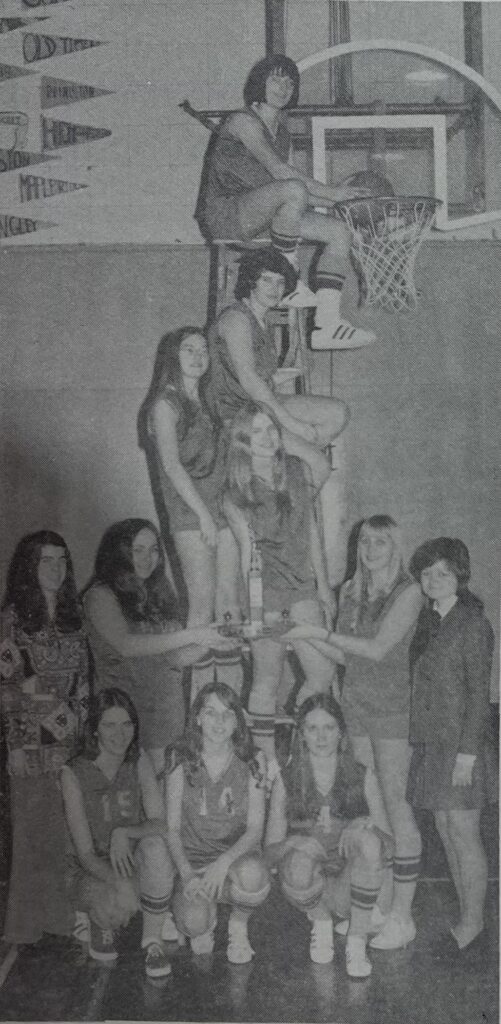

One accomplishment of the women in CSSS was getting a woman’s football game going. In November of 1969, there was to be held a football game between the grade 11 and 12 girls.[18] The girls were well prepared for this game and spent a lot of time practicing as it was important to them.[19] This importance was because it meant they “invaded the last stronghold of man.”[20] Football was clearly perceived as a man’s game in Chilliwack, but the girls were able to break that barrier; it was a celebrated accomplishment.

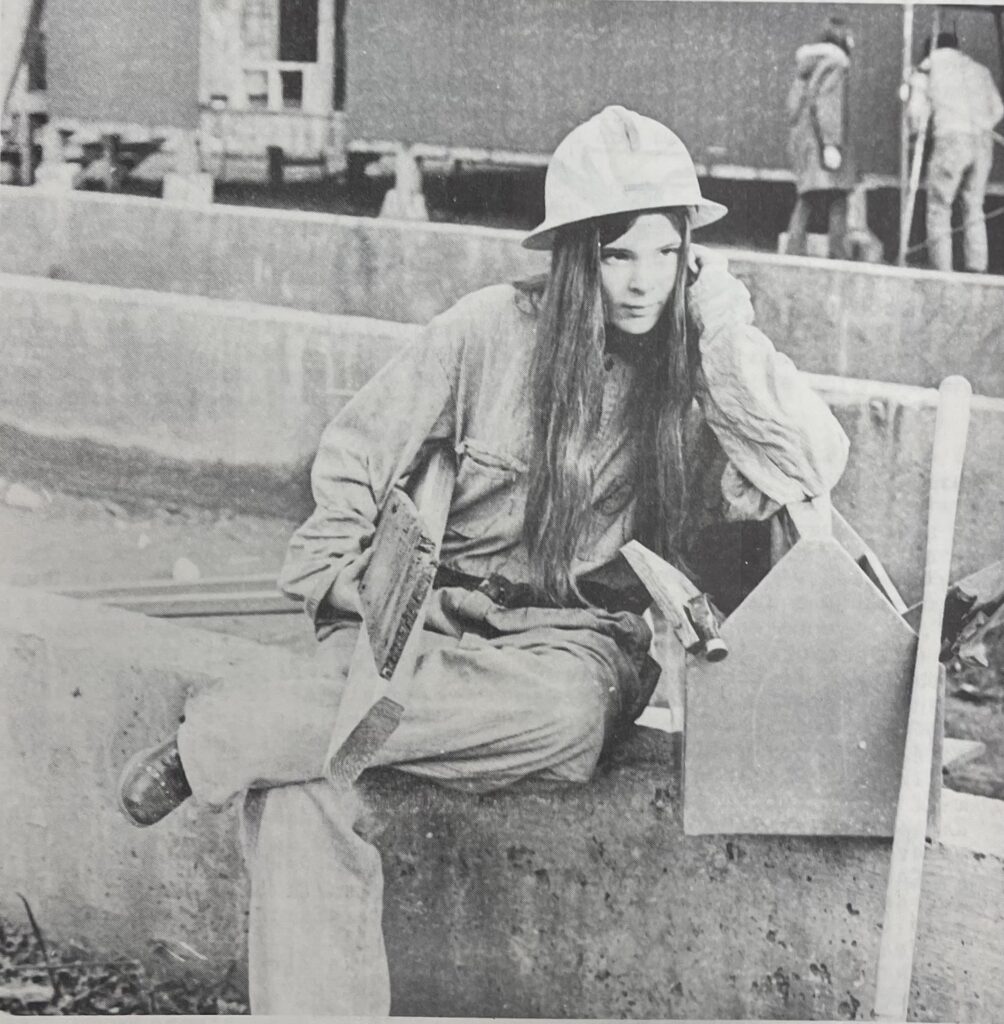

Female students embraced what they perceived to be their own roles in society and it was clear that gender norms were changing. Students like Elsie Friesen looked forward to being mothers, so much so that she said, “God could not be everywhere and therefore he made mothers.”[21] While this is good humour, it is also clear that she believed in the importance of motherhood. Other students, like Diane Barritt, were known for their politics and protest. Diane was known for protesting Amchitka, and other students were known for similar things.[22] Women also no longer felt constrained to what they used to be expected to wear. The students recalled the days when they were expected to wear a dress on a date; they also recalled the time they had the freedom to wear their first two-piece swimsuit.[23] They recalled when it was wrong to kiss on the first date and the days when only married women could have babies.[24] Times were changing in Chilliwack and students were aware of and with the changes.

When it came to dropout rates at CSSS, only a third of the dropouts were girls.[25] At least half of the girls who dropped out went to other schools, the rest dropped out due to other circumstances whether marriage, work, or illness.[26] One reason there were so many boy dropouts was because of the semester system that was in place at CSSS; dropouts knew they could always come back and finish the semesters they needed to finish if they wanted to graduate.[27] Because of all this, Joanne Haan who was the editor of the Tatler, argued that it was not true that females were the weaker sex.[28] She argued that because there were more male dropouts, and many of them were not able to come back, that the boys were not as strong as they thought they were.[29] When it came to learning, Joanne felt that women were the stronger sex.

The perception of male students was also changing at CSSS. The narrative of men being the superior workers was challenged by the women, as they argued that if men were the better workers, the honour role would be male-dominated; instead, it was massively female-dominated.[30] There was the idea that males used to be dominant, and females submissive, but that had changed.[31] There was also the idea that guys used to be guys and girls used to be girls, but that had changed.[32] Rather, the idea of what a guy was or was supposed to be had changed. However, the boys at CSSS still dominated the sports world. In every annual, much more attention was placed towards the boys’ sports than the girls’ sports.

Overall, the perceptions of gender were changing and had changed at CSSS. This even carried out into the broader community. Chilliwack did not have any women’s liberation protests of note. It is likely that if any students participated in demonstrations, they would have left Chilliwack to do so. However, Chilliwack voted in their first female member of the township council in December of 1970, Dorothy Kostrzewa.[33] In an election where the other councillors voted in had agricultural backgrounds, which was important in Chilliwack, Kostrzewa won the most votes out of anyone running in the election.[34] She said, “It looks as though the women’s liberation movement has finally made an appearance in Chilliwack.”[35] So, the perspectives of students were changing, and the perspectives of the broader community were changing.

[1] Cindy Ryall, “Editorial,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[2] Cindy Ryall, “Editorial,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[3] Cindy Ryall, “Editorial,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[4] Cindy Ryall, “Editorial,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[5] Judy McLeod, “Women’s Liberation,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[6] Judy McLeod, “Women’s Liberation,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[7] Judy McLeod, “Women’s Liberation,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[8] Judy McLeod, “Women’s Liberation,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[9] Judy McLeod, “Women’s Liberation,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[10] Judy McLeod, “Women’s Liberation,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[11] “Judy McLeod, “Women’s Liberation,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[12] Judy McLeod, “Women’s Liberation,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[13] Judy McLeod, “Women’s Liberation,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 3. .41

[14] C.H. “P.O.P.” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, “Tatler,” December 3, 1971. 10.

[15] C.H. “P.O.P.” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, “Tatler,” December 3, 1971. 10.

[16] C.H. “P.O.P.” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, “Tatler,” December 3, 1971. 10.

[17] C.H. “P.O.P.” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, “Tatler,” December 3, 1971. 10.

[18] Frontiersman, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, 1969-1970.

[19] Frontiersman, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, 1969-1970.

[20] Frontiersman, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, 1969-1970.

[21] Frontiersman, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, 1973-1974.

[22] Frontiersman, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, 1972-1973.

[23] “Remember When” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, “Tatler,” December 3, 1971, 8.

[24] “Remember When” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, “Tatler,” December 3, 1971. 8.

[25] Joanne Haan. “Editorial,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November 12, 1971, 3.

[26] Joanne Haan. “Editorial,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November 12, 1971, 3.

[27] Joanne Haan. “Editorial,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November 12, 1971, 3.

[28] Joanne Haan. “Editorial,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November 12, 1971, 3.

[29] Joanne Haan. “Editorial,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November 12, 1971, 3.

[30] “How Come?” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, November, 1972. 4. .41

[31] “Remember When,” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, April 14, 1972, 7. .33

[32] “Remember When” Tatler, Chilliwack Senior Secondary School, “Tatler,” December 3, 1971. 8.

[33] “Democracy in action,” Chilliwack Progress, December 16, 1970, 16, https://theprogress.newspapers.com/image/77075394/.

[34] “Democracy in action,” Chilliwack Progress, December 16, 1970, 16.

[35] “Democracy in action,” Chilliwack Progress, December 16, 1970, 16.